Mykhailo Drahomanov – a grand and paradoxical figure in Ukrainian intellectual history, politics, culture, science, and education. Also – an underrated intellectual who uniquely combined ideas of socialism, liberalism, and anarchism. The greatest Ukrainian advocate of 19th-century European civilization and culture. At the same time, Drahomanov was the first political thinker to unequivocally link the Ukrainian project with European progress. It has been 130 years since his death. Yet, there is still no complete collection of his works or even a preliminary academic systematization of them. The least is known about his emigration period, more precisely – the Geneva era (1876–1889). The Swiss years are the key to understanding Drahomanov as one of the greatest Ukrainian thinkers. This period is the focus of a Swiss-Ukrainian project that united scholars from the Institute of History of Ukraine of the NAS of Ukraine and the University of Lausanne under the leadership of corresponding member of the NAS of Ukraine Oleksii Yas and Professor Bela Kapossi. This project started at the beginning of 2025 within the framework of the international competitive program of the National Research Foundation of Ukraine and the Swiss National Science Foundation, funded by the Swiss side.

What should one know about Mykhailo Drahomanov as one of the most outstanding Ukrainian and European political thinkers of the 19th century? Was it a coincidence that he chose Switzerland when emigrating from the Russian Empire? What did he envision as a successful Ukrainian national project? Oleksii Yas was asked about all this by the press service of the NAS of Ukraine.

Corresponding Member of the NAS of Ukraine Oleksii Yas. Photo provided by Oleksii Yas

– Oleksii Vasylovych, why specifically Mykhailo Drahomanov? What makes this figure interesting? And what might we Ukrainians not know or remember about him that we should?

– Thank you, that’s an interesting question. Let’s think about it. First: Mykhailo Drahomanov was born in 1841 and lived almost 54 years. That’s 14 years less than Hrushevskyi and 6 years less than Franko. There is a multivolume edition of Franko’s works – over 50 volumes and additional ones. About half of the planned fifty volumes of Hrushevskyi’s works have been published. But what about Drahomanov’s texts? His bibliographic index lists about a thousand works. According to various experts, this amounts to 20 to 30 full-fledged, i.e., large volumes. And to this day, they have not even been preliminarily outlined... That’s one aspect.

Second: Drahomanov was an intellectual of very large scale. By his interests, he was an encyclopedist. Like Hrushevskyi and Franko. He was interested in the history of literature, culture, politics, ethnology, folklore studies, educational, linguistic, and confessional issues. He was the author of memoirs and a large epistolary legacy. But most importantly – Drahomanov was the greatest Ukrainian supporter of European culture. Yefremov once said about him: “The ambassador of Ukrainian culture at the European court.” In this sense, Drahomanov’s history is largely not only the history of Ukraine but also the history of Europe. Because Drahomanov thought very interestingly, uniquely, and unexpectedly originally. He is difficult to perceive. He considered the world and Ukraine as part of a gradual universal, cosmopolitan process. And he asserted that the success of the Ukrainian project is to be among the peoples of Europe, within European civilization. This is another reason to be interested in Drahomanov.

And third, worth mentioning. He was a passionate supporter of comparativism. Yes, 19th-century comparativism. Yes, following the example of the famous theory of wandering histories by Theodor Benfey. Drahomanov compared peoples, countries, different epochs, facts, personalities, phenomena, and processes. And these are interesting comparisons. Sometimes stereotypical, but sometimes quite apt. Moreover, we are dealing with a personality who is not one-dimensional. 19th-century intellectuals are usually imagined very simplistically. For example, if a person supports progress, that progress is interpreted as a linear movement from lower to higher levels (the simplest example). But with Drahomanov, it is not so. For instance, he assessed the Paris Commune of 1871 as the sprouts of an advanced society, but at the same time, in one of his letters, he wrote that it arose “from a lack of oxygen,” i.e., a lack of political Freedom (capitalized!) in French society. In his opinion, the Paris Commune was progressive in some respects, but on the other hand – conversely: in social matters, in the light of revolutionary confrontation, he evaluated it skeptically, and even somewhat negatively. Such heterogeneity... Very often we pick out from Drahomanov’s texts some separate moments, fragments of his thinking, while probably the most insightful interpreter of his work – Ivan Lysiak-Rudnytsky – noted: “Drahomanov is a systemic thinker.” Unfortunately, we often forget this.

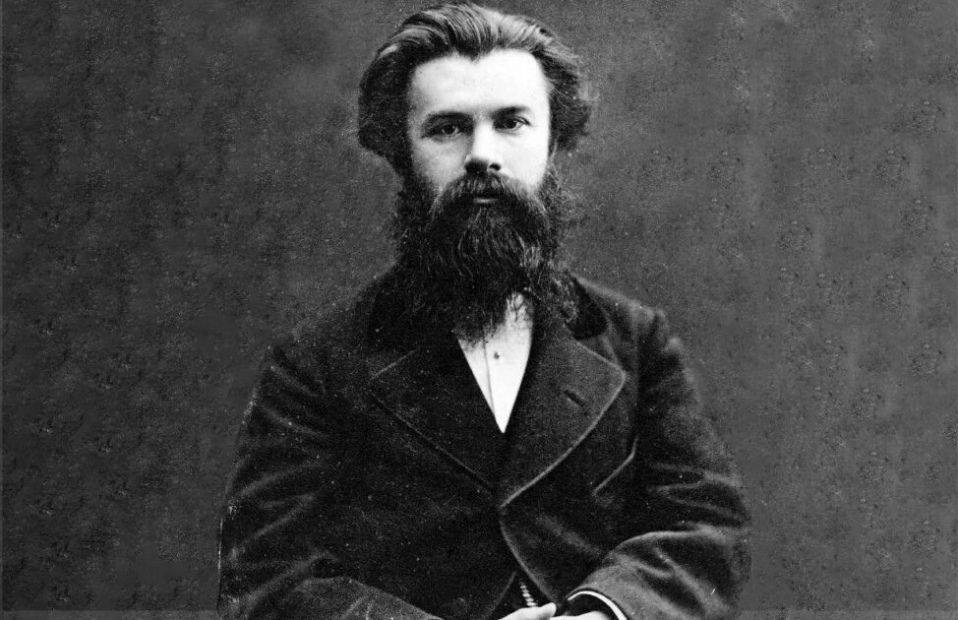

Mykhailo Drahomanov

– You mentioned Drahomanov as a multidimensional thinker from whom one cannot isolate individual ideas. But in recent years, his phrase about the end of the 19th century has become especially popular, when the Hetmanate, by the hands of the Russian Empire, settled scores with its old enemies – the Ottoman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth – and the main problem for the Hetmanate, for Ukrainians, became the Russian Empire itself. What else from his work might be relevant for modern Ukraine?

– The last idea you mentioned was expressed by Drahomanov in his famous work with the metaphorical title “Lost Time. Ukrainians under the Moscow Tsardom (1654–1876)” (published posthumously in 1909). First, it is important to understand the context of this work. First, why “lost time”? Drahomanov believed that the history of Ukraine moves within the orbit of European culture. Yes, with delay, with problems, but it moves. But he considered the Pereiaslav Agreement of 1654 abnormal because it united republican Zaporizhzhia and the boyar-tsarist Moscow state. That is, there was a gradual disruption of this European development program. A departure from European models – culturally, politically, socially – mostly during the 18th and further into the 19th century. However, one cannot say that this development completely froze or stopped. At least, that was Drahomanov’s belief. In 1861, the peasants were freed, and this is important. But there was no political freedom, no political rights; emancipation was widely delayed in almost all its spheres – cultural, educational, social, economic, gender... The stratum of people (zemstvos) who acted as enlighteners was very small. The Hromada movement with its cultural and scientific program in many respects unfolded as a way to modernize and improve the empire. The Hromada members sought to create initial opportunities for the further development of Ukrainian identity... Because what is progress for Drahomanov? It is not the achievement of an ideal society or some higher future, as many positivists thought. It is the improvement of social nature. How? First, the person must become better, and second, the community must radically change, overcoming its path of historical evolution. Is this possible without the basic foundations of social Freedom? Of course not. Therefore, “lost time” is time lost for such political, cultural, and social development. But the reform of 1861 did happen, and later, in the early 1870s, Drahomanov wrote: “our cause is largely done” by this reform, and now we must “move along the road of European progress.” But what next? The Polish uprising of 1863 occurred, and as a result – note – a government and public campaign against... Ukrainophiles and a ban on... the Ukrainian language. Despite it being a Polish uprising, Polish publications were allowed in the Russian Empire, but Ukrainian ones were banned. After the Petersburg “Osnova,” almost nothing was published. A paradox! Imagine how painfully the Ukrainian activists of the time perceived such a situation... But that’s not all. A secondary modernization began in the Russian Empire, delayed, slowed, contradictory. However, at some stage, progress became half-hearted, went astray, as contemporaries wrote... Drahomanov sincerely hoped the situation would change and, albeit belatedly, the empire would move “along the common road of universal progress.” But this did not happen, at least not as hoped immediately after 1861. In 1876, the Ukrainian language was banned again. Additionally, the revolutionary movement radicalized: terrorist practices, agitation, going to the people began. In response – government repressions. 1881 – the assassination of the tsar. And again government repressions against revolutionary terror. Was this good for progress? According to Drahomanov – certainly not. Already in emigration in Geneva, he wrote: “We will not dance the cannibals’ dance over the enemy’s corpse.” That is, he had a negative attitude toward terror. But at the same time, he believed a person has the right to defend themselves, their home from invasion, provocations by the “robbers of the Third Department” [political police].

Thus, “lost time” is a very interesting and apt metaphor. But Drahomanov has another one – “plebeian nation,” i.e., a nation that essentially lost its aristocracy or, using modern terminology, its elite. Due to Russification, Polonization, Germanization. How did this metaphor arise? Drahomanov wrote that European socialist organizations, primarily French ones, must consider the needs and interests of non-state nations. Initially, he applied the metaphor “plebeian nation” to the practices of Western European socialists and then transferred it to Ukrainian lands and applied it to Ukrainians. Later, in the last quarter of the 20th century, a sharp debate took place in the Ukrainian diaspora about the complete/incomplete, full/incomplete nation regarding the history of Ukraine and Eastern, and partly Central Europe. To some extent, such reflections stem from this metaphor of Drahomanov.

So, Drahomanov is a very interesting, original thinker who should not be perceived simplistically or one-dimensionally. His texts can tell a lot about the past of the second half of the 19th century. And most importantly: he shows that despite everything, Ukraine in various epochs lived a European life under very unfavorable circumstances. Some scholars – for example, Omelian Pritsak and John Reshetar – even wrote about the Geneva stage of the Ukrainian national movement. That’s how highly they valued his activity in emigration.

– Well, if there were Drahomanovs and Kosachs, then Ukrainians probably have not completely become plebeians yet.

– Absolutely. Any thesis must be taken relevantly. And Drahomanov’s observation should not be overly generalized.

– You mentioned Geneva, so I cannot help but ask: what is the reception of Drahomanov’s figure and legacy in Europe? Specifically, in Switzerland. And how did your joint project with Swiss colleagues come about?

– I partly already told you about a certain paradox regarding Drahomanov, his reception, and study. A complete edition of his works still does not exist, and the most comprehensive collections were published over 100 years ago. We can also mention the project of our colleague from the Institute, Valentyna Shandra: in 1991, she and Rostyslav Mishchuk published a one-volume selection of Drahomanov’s works. There were other projects, sometimes several books, but with very modest, sometimes minimal scholarly apparatus. Additionally, memoirs about Drahomanov, his autobiography, Austro-Russian memories, separate works, and several books of selected works were published. But these were mostly separate projects. They covered selected segments of his legacy. There were intentions to publish an academic edition of Drahomanov’s works. For example, in 1988, these intentions were declared in the diaspora, later in the 1990s and in independent Ukraine. However, unfortunately, this was not realized. On the other hand, the 2011 bibliographic index lists over 5,000 publications about Drahomanov. Several dozen books about him have been published, and at least twenty dissertations defended in Ukraine and abroad, including Harvard and Oxford. Such a paradox... At the same time, the least is known about his Geneva period. But to understand Drahomanov, one must understand why he chose Switzerland. Here begins a separate story of our project...

The idea came from our Swiss colleagues, more precisely from Ukrainian scholars who found themselves in Switzerland due to the Russian-Ukrainian war of 2022. We are talking about our colleague from the University of Lausanne, Anastasiia Shevchenko. For Switzerland, Drahomanov’s figure is very interesting because he placed it at the center of Europe. Why? Imagine the 19th century: the Victorian era, industrial boom, urbanization, scientific and technical progress, spatial distances becoming closer... Remember Jules Verne – “Around the World in 80 Days” – in days, not years! The world was rapidly expanding its boundaries, and humans were significantly changing. 1851 – the first, as Drahomanov said, comprehensive cosmopolitan event: the World Exhibition in London. The 1860s – the unification of Germany, the unification of Italy. A new map of Europe. Drahomanov first came to Europe on a three-year scientific journey, and from 1876 became an emigrant. What interested him? Europe from the perspective of European Freedom. Where was Freedom most complete in Europe? He made an imaginary ranking of the states of the then world. And first place – Switzerland. Why? Because it is a federal state without a dominant state nationality, where several languages coexist peacefully. Drahomanov wrote: two Italian cantons of Switzerland supported the Italian Risorgimento but did not want to join Italy and decided to remain in Switzerland. Another feature – cantonal democracy and extremely large rights of local communities. Free language, educational, and cultural policy. Something unimaginable in the Russian Empire, especially with its bans and repressions. Drahomanov’s eldest daughter, Lidiia, recalled: when friends or emigrants visited her father and worried, for example, about luggage or left travel items, he smiled and reassured them: “You are in Switzerland, the Swiss are conscientious and honest people...” And most importantly: Switzerland was for him almost the ideal balance between individual Freedom and community Freedom. And this Freedom was ensured by the Swiss state system. Because the state, in Drahomanov’s understanding, is rather a union, a broad and large agreement about coexistence between the individual and the community (or several communities). Finally, Switzerland had universal suffrage (from age 20). At that time, as British historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote, there were only four such countries in the world [Switzerland, France, Denmark, USA]. Moreover, in Catholic cantons, even the clergy was elective. By the way, Drahomanov was also famous for bequeathing to be buried according to Protestant rites, although he came from an Orthodox family and spent his last years in Orthodox Bulgaria. Was he that religious? Not at all. This was a symbolic gesture of an intellectual who recognized that Protestantism played an important, fundamental role in achieving European Freedom on the field of universal progress.

– Max Weber wrote a whole book about this.

– By the way, Max Weber once noted and appreciated Drahomanov’s 1884 constitutional project, calling it one of the best at that time...

– This, actually, also relates to the question of reception.

– The reception was very complex and heterogeneous. Drahomanov first came to Switzerland in 1873. It was a very short trip to Zurich, where, as they said then, there was a large “Russian” (in quotes!) colony. In reality, it was not Russian. It consisted of subjects of the Russian Empire belonging to many nationalities. Why there? The secret is very simple – the local university and the Polytechnic School in Zurich were the first to admit women. More than a hundred young women from the Russian Empire enrolled there (besides them, there were Americans and representatives of many European countries) because there was no need to take entrance exams. What was happening in this community of female and male students, and nearby – political emigrants from the Russian Empire, where Drahomanov arrived? They were divided, roughly speaking, into two radical camps: supporters of the narodnik Lavrov (a sympathizer of Marx) and supporters of the anarchist Bakunin. Some later became propagandists, others – terrorists (as Drahomanov wrote, bombers). But both groups perceived him as a retrograde... Because he proposed to first gain political Freedom, and then everything else. Without Freedom, normal social evolution is impossible. This was Drahomanov’s position.

European reception of Drahomanov was even more complicated. There were different circles. Among them – a rather numerous anarchist one. With one former anarchist – Count Angelo de Gubernatis, editor of the Italian magazine “Revista Europea” – Drahomanov cooperated, publishing a whole series of articles in this journal. He was friends with the famous geographer Élisée Reclus, who once participated in the Paris Commune. He was friends with Swiss naturalist Karl Vogt. Vogt was among the few German-speaking authors who negatively assessed the imperial project of Germany (the Second Reich) because this unification occurred by violent means. So, on the one hand, anarchists treated Drahomanov cautiously, but in many respects sympathized with him. Socialist perception of Drahomanov was also not uniform because in many aspects he was inconvenient for them. For example, he did not accept economic materialism. In a letter to Yulian Bachynskyi, author of “Ukraine Irredenta,” he, as a rationalist, wrote that human life cannot be explained only through economic problems. In this sense, economic materialism and Marx’s class struggle, according to Drahomanov, are true metaphysics! He clearly wrote this to Bachynskyi... At the same time, Hrushevskyi compared Drahomanov with the socialist revisionist Eduard Bernstein. Bernstein also emigrated from Germany to Switzerland, but a few years later than Drahomanov.

And there is another very interesting reception – Russian and Ukrainian. Almost all Ukrainian parties of leftist, socialist, or liberal orientation of the late 19th – early 20th century largely oriented themselves on Drahomanov’s ideas. Everything became very complicated later – after the revolution and at the beginning of Ukraine’s war with Bolshevik Russia in 1918. By the way, Drahomanov unexpectedly turned out to be “one of their own” for Russian constitutionalists – the Constitutional Democratic Party of People’s Freedom. On the eve and during the Russian Revolution of 1905–1906, the liberal magazine “Osvobozhdenie” published collections of his works in thick volumes. So many activists simultaneously did not accept Drahomanov and adapted his ideas to their political needs and interests. They considered him a socialist, liberal, atheist, religious freethinker, Protestant, conservative, revolutionary, evolutionist, gradualist, nationalist, and at the same time cosmopolitan... Everyone picked a convenient kaleidoscopic moment or mosaic fragment for themselves. The situation changed after 1918, and even more after the defeat of the Ukrainian Revolution of 1917–1921. For example, Drahomanov’s idea of a federation of communities and unions, close to Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s ideal, became the subject of very sharp criticism and even total denial of Drahomanov’s legacy. According to Drahomanov, the federation was a dynamic balance between the rights of the individual, communities, local unions, elected self-government bodies that delegated limited and selected rights to the central bureaucracy. Moreover, for a certain time and with many constitutional limitations. And although Drahomanov’s views were not purely socialist – it was a very complex mix of anarchism, socialism, and liberalism (European model) – they eventually faced widespread nationalist and conservative criticism. Dontsov and Mukhin extremely negatively perceived Drahomanov’s calls for universalism, humanism, and cosmopolitanism. In their opinion, this...

– ...hinders the Ukrainian national cause?

– ...harms, destroys, distracts from revolutionary or sacrificial struggle. Therefore, Drahomanov’s life story and intellectual biography were perceived and represented controversially. Political experience of the 20th century was involuntarily projected onto Drahomanov and his ideas. It is no coincidence that later researchers wrote about him: earlier – Stepan Tomashivskyi in his study “The Tragedy of Drahomanov” (1925), and in our time – Anatolii Kruglashov in “The Drama of an Intellectual...” (2000). Although much has been written about Drahomanov’s biography, it still needs to be de facto comprehended and read from another perspective – Swiss and European. Drahomanov’s life story is very interesting and peculiar. And much more needs to be learned about it, sources found, facts checked, other testimonies read and systematized, and finally understood...

– What gaps does your project aim to fill? What are your priorities?

– We focused primarily on the Geneva, Swiss period. Our project is “Mykhailo Drahomanov: Switzerland on the Ukrainian Intellectual Map of Europe”. Why this title? It is not about mental geography or mental maps, although they cannot be excluded. A map is a way to tell the story of Drahomanov in the center of Europe, in Switzerland, which for him embodied the greatest European Freedom.

By the way, what were the next countries in his imaginary ranking? Second place – the British monarchy, surprisingly. Why? Thanks to a very strong layer of corporate and municipal rights, traditions of parliamentarism (what is worth is the phrase “His Majesty’s Opposition”). The king is essentially the guarantor of constitutional rights and freedoms. Another point in favor of Great Britain – an efficient bureaucracy. Not like in Switzerland, but still. And also – developed British philanthropy. And, of course, respect for women and the beginnings of women’s emancipation.

Third place for Drahomanov – the United States. You might say: that’s not Europe! But Drahomanov believed it was the transfer of the neo-European project, Dutch and English legal traditions, models of constitutionalism – to the colonies. Constitutional traditions of North Carolina, Virginia date back to the 17th and 18th centuries. Moreover, for Drahomanov, the federal union of states and the special role of the Senate were very important. But most importantly – the best-written individual rights in the American constitution.

Next places are occupied by the Netherlands, Belgium, and the Scandinavian countries (including Denmark). The Netherlands – as a former federal state. Belgium – because there they tried to equalize the rights of Flemish and French languages in education and culture. Scandinavia – because there was no very strong centralist system, so decentralization prevailed, and special relations between communities and individual subjects developed.

This is how Europe appears in Drahomanov’s imaginary world. The idea of our project is to understand this world: both Drahomanov himself and his vision of Europe. Because Drahomanov’s ideas are part of the intellectual history of Europe. And to comprehend this, we must first try to find out how Drahomanov lived in those times. This turned out to be a very difficult task. He left behind many texts. The entire life of one scholar is hardly enough even to master them at a basic level. The scale of Drahomanov is exactly such. So we thought, consulted with colleagues, what to do with all this? Initially, the project idea was conceived by our colleague from the University of Lausanne – Anastasiia Shevchenko. By the way, she and her Ukrainian colleagues in Europe launched a very important initiative “Ukrainian Scientific Diaspora.” The main idea is to show how Ukrainian scientists abroad can join and cooperate in our modern projects. This initiative, a de facto informal network, already unites several hundred scholars. For wartime and, obviously, post-war Ukraine, this is a very important, instructive, and interesting experience.

With warm feelings, I must mention another partner and colleague – Professor Bela Friedrich Kapossi of the University of Lausanne, a talented Swiss historian who is a sincere friend of Ukraine and Ukrainians. In 2022–2023, when it was hardest, he organized several conferences and events with Ukrainian refugee scholars to present their achievements and works, and helped them adapt abroad in every possible way.

But I must also say about Ukrainian colleagues. In our team, there is corresponding member of the NAS of Ukraine Yaroslava Vermenych, an excellent specialist in regional studies and historical geography. She has large-scale conceptual thinking and amazing work capacity, as evidenced by her numerous books.

Oksana Yurkova, a brilliant source specialist. Probably one of the best in Ukraine. She knows very well the legacy of Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, primarily as the author and leader of the project Electronic Archive of Mykhailo Hrushevskyi. So the idea of Drahomanov’s archive was proposed by Oksana. We faced the problem: how to organize materials, especially in the case of Drahomanov with his sea of texts? After all, any project eventually ends. And then what? Perhaps an electronic platform – initially as an archive – is a foundation for the future. To try to continue working in this direction or even broader – in the field of intellectual, political, and cultural history of the 19th, and possibly the 20th century. Using these developments.

Finally, I must mention Svitlana Blashchuk, a researcher with great talent in digital humanities. The digital architecture of our electronic archive is built on the New Zealand library system Koha. Believe me, it is very difficult. Svitlana and Oksana specially studied to develop a digital repository model and adapt it to our needs. Svitlana essentially acquired a new profession for this! I note that most of our library systems are still based on modified Russian software products. This, unfortunately, is also a significant problem. Our team consciously, though not without pain, chose a different path.

By the way, cooperation with Swiss colleagues also allows us to see and understand that there is another scientific culture. Personally, I lacked this because it so happened in my life that I rarely had contact with scholars from other countries. In my opinion, this is a very interesting and instructive experience.

Our project has several tasks. One of them, of course, is to prepare a book about Mykhailo Drahomanov. We have already written a number of articles – in an experimental format. It is necessary to involve other European and Ukrainian colleagues in this work. Some of them participated in scientific seminars in Lausanne and Kyiv, organized by our team. They have their visions, and this allows showing Drahomanov from different scales and angles. In the process of work, we also discovered that another scientific culture implies a different style of communication: primarily, there must be other forms of informational support for the project. Well, and the digital component of our project is also very important because it is a way to fill certain gaps.

Of course, much still needs to be done, many texts of Drahomanov read and comprehended, as well as understanding the accompanying contexts. And most importantly – to imagine his environment – Geneva and broader European life, with whom he communicated, contacted, what influences he experienced and on whom he influenced... Apparently, this is a considerable number of people. For example, his eldest daughter recalls that he was a member of several scientific societies in Geneva. The immediate question: which ones? This is also not easy to find out, although there are already some clues... Anastasiia Shevchenko is currently working in Swiss archives. We communicate constantly, so we know that every finding is gained through a very difficult path and requires prolonged work. Especially considering the linguistic, cultural, technical, and other differences of the Swiss archival network compared to Ukraine. And finally... Our team will make every effort to successfully implement the project. The main goal is to present Drahomanov not only as a Ukrainian but also as a European thinker.

Logo of the Mykhailo Drahomanov electronic archive. Source: drahomanov.history.org.ua

Interviewed by Snizhana Mazurenko